Antarctica and the Arctic are the two coldest places on earth. The polar regions are known for their vast, glittering icescapes, uniquely adapted wildlife and snow-capped peaks, so it may come as a surprise that Antarctica is colder than the Arctic. In fact, Antarctica is much colder than the Arctic, and there are several good reasons.

The main reason that Antarctica is colder than the Arctic is that Antarctica is a landmass surrounded by ocean, and the Arctic is an ocean surrounded by landmasses. Antarctica also has a much higher average elevation than the Arctic, and the Antarctic Ice Sheet is bigger and thicker than the ice in the Arctic.

To understand why Antarctica is so much colder than the Arctic, let’s start by looking at some of the major differences between the polar regions.

How is Antarctica different from the Arctic?

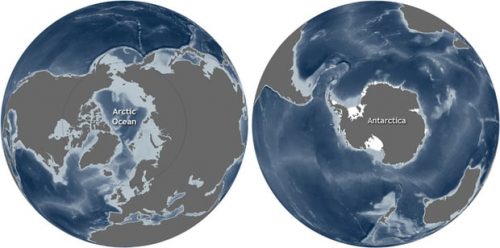

Antarctica is a landmass surrounded by ocean and the Arctic is an ocean surrounded by land

The Arctic region is dominated by the Arctic Ocean, which covers the northern extreme of the globe from Canada to Russia and northern Europe. The Arctic Ocean is surrounded by several landmasses including Norway, Russia, the United States (Alaska), Canada, Denmark (Greenland), and Iceland.

By contrast, Antarctica is a continent completely surrounded by the Southern Ocean. It is quite isolated from the rest of the planet – the closest continent, South America, is around 1000km (600 miles) away.

Antarctica has more ice

Around 90 percent of the ice on the planet is in Antarctica. Antarctica is covered by an enormous, permanent ice sheet twice the size of Australia, or roughly the size of the United States and Mexico combined. The Antarctic Ice Sheet is thousands of metres thick. This glacier ice, which originally fell as snow and hardened into ice over millennia, has an average depth of 2,160 metres (7000 feet), and is up to 4,776 metres (15, 669 feet) thick in places.

The second-largest ice sheet on the planet is the Greenland Ice Sheet, which is in the Arctic. However, this ice sheet is only one eighth the size of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. While parts of the Greenland Ice Sheet are up to 3,000 km (9,842 feet) thick, the average thickness is around 2,135 metres (7,005 ft).

How cold are Antarctica and the Arctic?

What is the coldest temperature in Antarctica and the Arctic?

The coldest temperature ever recorded on Earth was in Antarctica at -93.3°C (-135.9°F). Scientists registered this staggeringly cold temperature on the East Antarctic Ice Sheet in 2013, after analysing 32 years of satellite data.

The coldest temperature in the Arctic was 23.7°C (42.6°F) warmer than the Antarctic record. In 2020, scientists confirmed the coldest temperature in the Arctic was in Greenland in December 1991, when the mercury dropped to a very chilly -69.6°C (-93.3°F).

What is the average winter temperature at the North and South Pole?

The average winter temperature at the North Pole is -40°C (-40°F). This is seriously cold, but not quite as cold as the winter average at the South Pole, which hovers around -60°C (-76°F)!

Why is Antarctica so much colder than the Arctic?

The Arctic Ocean keeps the atmosphere warm

Water warms and cools more slowly than land, so the ocean and areas near the ocean have fewer extremes of temperature. Even when it’s covered by ice, the relatively warm temperature of the Arctic Ocean has a moderating effect on the climate, helping to keep the Arctic slightly warmer than Antarctica.

In Antarctica, the ocean has a moderating effect on the climate near the coast. The Antarctic Peninsula is often called Antarctica’s ‘Banana Belt’ due to its relatively warm temperatures, and other coastal areas of Antarctica are known for their lush moss forests and comparatively warm climates. However, temperatures across most of Antarctica remain extremely cold due to the cooling influence of the massive Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Antarctica has a larger ice sheet

Ice is cold, and Antarctica is covered by the largest ice sheet on earth. The bright, white surface of the ice sheet reflects most of the solar radiation (and heat) that reaches it back to space. The ice also cools the air directly above it, helping to keep Antarctica cool.

While the Greenland Ice Sheet has a similar effect, its much smaller size means that it has a less powerful influence on the Arctic climate.

Antarctica is at altitude

Antarctica is the highest continent on the planet, due to thick layers of ice that raise its average elevation to around 3,000m (9,800 ft). Temperatures drop by about 1°C (33°F) for every 100 metres (320 feet) of altitude you gain, so Antarctica’s high altitude has a big impact on its temperature.

Although the Arctic has many rugged mountain ranges and stunning alpine peaks, much of the region lies at sea level, on the Arctic Ocean.

Winds

Antarctica is the windiest continent on the planet, with winds reaching up to 327km/h (199 mph), almost three times stronger than hurricane force winds on the Beaufort Scale. These windy conditions mean that cold temperatures feel even colder in Antarctica due to wind chill.

Why are the poles so cold?

While Antarctica is much colder than the Arctic, both polar regions are generally much colder than the rest of the planet. There are several reasons for this, including:

1. Dark winters

For six months over the winter, the sun doesn’t rise above the horizon within the polar circle (66°30’ North and South). Without the warming effect of direct sunlight the poles get very, very cold.

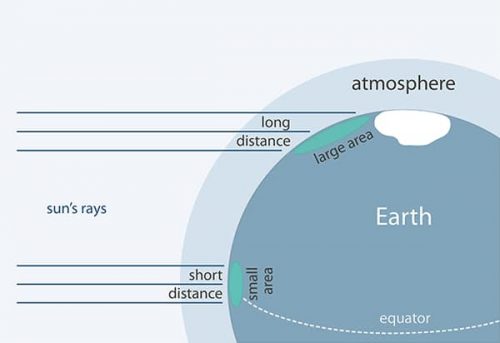

2. Angle of sunlight

When the sun returns to the polar regions in summer, they still receive less sunlight than other places on earth due to their position at the north and south extremes of the globe. In the polar regions the sun has to push through more atmosphere, and is spread over a bigger area than at the equator.

3. Lots of ice

Large reserves of ice have a cooling effect on the air temperature above the ice. Both the Arctic and Antarctica have large ice sheets and seasonal sea ice, both of which help keep the poles cold.

4. Large reflective surfaces

The white surfaces of ice and snow are highly reflective. They radiate most of the heat that reaches them back out to space, keeping the air above them relatively cool.

What is the difference between the North and South Poles?

From sea level to high altitude

The North Pole is located at sea level, in the middle of the Arctic Ocean. By contrast, the South Pole is high and dry on top of the Antarctic Ice Sheet, which is 2.8 kilometres (1.7 miles) thick in this area. The South Pole is so far above sea level that some people who visit experience altitude sickness!

What lies beneath

If you could lift the ice off the South Pole in Antarctica you would find a rocky landmass (or landmasses) with gorges, canyons and mountain ranges, much like the other great continents on our planet. If you lifted the sea ice off the North Pole, you would find the Arctic Ocean.

X marks the spot?

At the North Pole, the Arctic Ocean is frozen into huge plates of sea ice, which are constantly moving, so there is no official marker to mark its location. However, many visitors bring their own sign to commemorate the occasion!

The exact location of the South Pole is marked with a stake, which is stuck into the ice. There is just one slight problem: the ice sheet moves about 10 metres (30 feet) each year, so the stake has to be moved annually to remain accurate!

Can you visit?

It’s possible for tourists to visit the North Pole by air or sea. But the only way to stand on the North Pole is to step out on floating sea ice!

The South Pole is so remote that no tourists can visit, but there is an Antarctic research station at the South Pole, where a small number of people live each year. The Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, named for the first two expedition leaders to reach the South Pole, supports 150 researchers and support staff in summer, and 50 through the winter. Most Antarctic travellers visit the Antarctic Peninsula, which you can reach with a short sea crossing or flight from South America.

What animals live in the Arctic and Antarctic?

The Arctic

Polar bears

Polar bears are the largest land carnivore in the world and the largest member of the bear family. They spend most of their time on ice floes in the northern Arctic, feeding primarily on ringed seals. These impressive predators are also incredible swimmers, with records of polar bears swimming some 80 km (50 miles) from any land or floe.

Musk Ox

Musk oxen have historically been associated with the hunting cultures of early mankind. Their meat and hides were used for food, clothing, and shelter, while the horns and bones were carved to make tools and crafts.

Arctic Fox

Smaller than the familiar red fox and with more rounded ears and muzzle, the arctic fox is distributed all around the Arctic in high latitudes and out on the open tundra. Arctic fox are well-adapted to the arctic environment, and remain active all winter and live in the open.

Arctic hare

The arctic hare is one of five species of Lagomorphs (the order that includes rabbits, hares and pikas) that live in the Arctic. Their fur is longer and finer than most temperate hares, and they have shorter ears. Fossil remains of Lepus Arcticus have been found in a 12,000-year-old Eskimo site in northern Greenland. The Inuit consume the meat of arctic hares and use the hide for clothing and bandages.

Reindeer

Reindeer are vegetarians and they eat most available types of vegetation, including new-growth leaves, lichens and even fine twigs. Their coat is very heavy and dense, predominantly brown to olive, although some populations in Greenland are almost completely white. The broad, flat structure of their feet allows the hooves to splay widely and act as snowshoes to travel over winter snows and the summertime spongy arctic tundra.

Walrus

The walrus is the largest pinniped in the Arctic, with distinctive tusks which they use as weapons, or levers to help them move around on land. Walruses are gregarious, and they may haul out in herds of up to several thousand individuals. During the non-breeding season groups are sexually segregated, and dominance is based on the size of their bodies and tusks.

Birdlife

There are only a dozen or so arctic birds that live in the Arctic all year round, including the gyrfalcon, raven, ptarmigan, snowy owl, redpolls, gulls (Ross’s and ivory), guillemots and the little auk. Most of the other 100 bird species that breed in the Arctic migrate to warmer climes to escape the harsh winter, including the Atlantic puffin, arctic tern and white-tailed eagle.

Whales

The bowhead, beluga and narwhal are year-round residents of the Arctic. However, many other whale species such as orca, humpback, and sperm whales are commonly found in these waters during the summer, visiting the Arctic to dine on the rich bounty of marine life in these productive waters.

Seals

There are a number of seals that live in arctic waters. The ringed seal is the most common and widespread seal in the Arctic. Harp seals are best known for the pure white coats of their young pups. Bearded seals have a circumpolar distribution and are permanent residents of the Arctic.

Find out more about some of the amazing animals you could spot on a voyage to the Arctic here.

Antarctica

Penguins

Eight of the world’s 18 penguin species live in Antarctica and on subantarctic islands. This includes Adélie, chinstrap, emperor, gentoo, king, macaroni and rockhopper penguins.

These flightless seabirds are extraordinary swimmers. With streamlined bodies like torpedoes, they use their flippers like wings for propulsion in the water, and their feet (and sometimes tail) to steer their course.

Penguins feed at sea, coming ashore to breed, rest and replace all their feathers at once in an annual catastrophic moult. With their mathematically precise huddles and pebble-stealing antics, they have developed some truly remarkable ways of thriving in the harsh Antarctic environment.

Seals

There are six Antarctic seal species that flourish in the cool haven of the Southern Ocean.

Weddell seals are the most southerly breeding mammal on Earth. Crabeater seals mostly eat krill – never crabs! Leopard seals are the second-largest of the Antarctic seals. The largest is the southern elephant seal, which is the largest seal on the planet. Fur seals are the only Antarctic seal that uses fur for insulation, in addition to blubber. Some Ross seal eyes are 7cm (2.75 in) in diameter, to help them see in the dark.

Krill

Antarctic krill (Euphasia superba) are small, shrimp-like crustaceans with large, black eyes and many small legs called thoracopods. There are an estimated 500 trillion Antarctic krill in the Southern Ocean, weighing 379 million tons. Scientists estimate that approximately half of this is eaten by the seals, penguins and whales that rely on krill as their main source of food.

Seabirds

Antarctica and the Southern Ocean are home to a diversity of seabirds, which often follow the ship as we sail. Several species of albatross can be spotted in these parts, including the royal, black-browed and wandering albatross, which has a wingspan up to 3.7 m (12 ft 2 in), the longest known wingspan on Earth. It’s not uncommon to spot giant petrels soaring past the bridge as we sail, or delicate Wilson’s storm petrels dancing on the surface of the water, foraging for copepods. Cape petrels, Antarctic prions, skuas, terns, cormorants and snow petrels also thrive on the Southern Ocean.

Whales

During the southern summer, antarctic waters are teeming with whales, which migrate to the southern latitudes to feed on a bounty of antarctic krill (Euphasia superba). Whales generally begin to arrive in Antarctica in November, reaching peak numbers in February and March.

One of the whales you’re most likely to see around Antarctica is the humpback whale. You might even be lucky enough to see one of them slapping their tails and pectoral fins on the water, or even breaching spectacularly, lifting their entire body out of the water! The relatively small, timid minke whales are slightly less common, but it’s worth keeping a look out for them taking a quick breath on the surface before diving deep. Orca (killer whales), fin whales and sei whales also cruise the Southern Ocean and occasionally surface, much to the excitement of everyone on board!

Find out more about some of the wonderful wildlife you could spot on a voyage to Antarctica here.

Words by Nina Gallo, AE Expeditions’ historian and certified PTGA polar guide.

Nina has been drawn to the polar regions since her first otherworldly experience of the midnight sun in 2002. Since then she has spent time in far northern Canada, the Himalayas, the Alps and deserts in America and Australia, always seeking out quiet, wild corners to explore. She feels immensely privileged to travel to these places and shares her passions for the natural world, human stories and adventure with all the wonderful people she meets. Nina is the author of Antarctica, published by Australian Geographic in September 2020.