All six seal species’ found living in Antarctica are classified as ‘least concern’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. This means they’re not classified as near-threatened, vulnerable or endangered. In short: their populations are in good health. From the delightful crabeater seals (that don’t eat crabs), to the immense southern elephant seals (the largest seals on earth), there are millions of seals in Antarctica, and none of them are considered endangered. This is great news for Antarctic seals, and it wasn’t always like this.

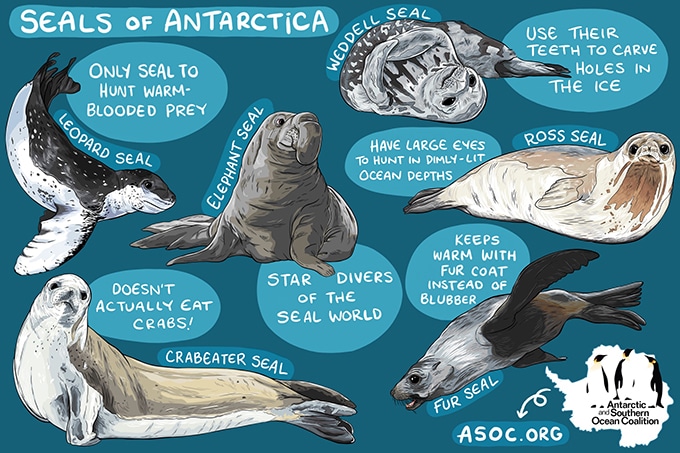

6 seals of Antarctica. Image courtesy of asoc.org.

Are fur seals endangered?

Antarctic (southern) fur seals are not endangered. In fact, they’re thriving! Especially in South Georgia, where almost 95% of the global population brings their boisterous breeding antics to the beaches every spring. But this wasn’t always the case.

From the late 1700s to the early 1900s, seal hunters flocked to South Georgia, the South Shetland Islands and other subantarctic islands, killing hundreds of thousands of fur seals for their pelts, which made popular linings for hats and coats.

During the 1800s fur seals in South Georgia were hunted to the brink of extinction – twice! In 1825, the British government introduced regulations to make the sealing industry more sustainable, and by the 1950s commercial fur sealing in the south was all but over. By 1976, the Antarctic fur seal population had rebounded to 100,000. In 2020, the estimated population is between 2 million and 5 million.

Are elephant seals endangered?

Elephant seals are not endangered today, but like fur seals, they were once the target of sealers. Their blubber was rendered to oil, which was used in paint, soap and candles. This continued until 1964, when their population had declined to the point that the industry was no longer economically viable.

How are Antarctic seals protected today?

Today, several binding agreements protect Antarctic seals from commercial sealing. In 1975, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES) came into force. This voluntary agreement ensures that wild animals and plants aren’t threatened by the commercial pressures of international trade. Today, 183 countries have signed on to CITES.

In 1978, seals received another layer of protection under the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals (CCAS), which sits within the Antarctic Treaty System. CCAS applies to all six Antarctic seal species. Under CCAS, no seals can be “killed or captured” for any purpose without government-issued permits. Violations of these laws can result in fines, and even jail time for repeat offenders.

Current threats to seal populations

Like all sea-dwelling species, seals face an uncertain future due to warming oceans, ocean acidification, increased plastic pollution and other threats, most of them caused by humans.

One of the biggest and most unpredictable threats to seals today is climate change. Warmer, more acidic oceans could lead to a cascade of impacts, and scientists are already noticing changes in Antarctic ecosystems. Scientists have reported changes in sea ice cover and fluctuating krill populations, which have been linked to a warming ocean. Both sea ice and krill are important for many Antarctic seals. Sea ice provides a habitat for single-celled algae and phytoplankton which form the basis of the Antarctic food chain. If less sea ice means less phytoplankton, this translates to reduced populations of krill (and other zooplankton) and less food for seals, whales and other animals at the top of the Antarctic food chain.

Other threats to seals include overfishing of krill and other Antarctic marine species, pollution and loss of habitat.

How can we help protect Antarctic seals?

Most scientists agree that the best way to support Antarctic seals is to establish a network of marine protected areas across the Southern Ocean. Marine protected areas are like national parks in the sea, where human activities are more strictly regulated than elsewhere.

In 2002, a group of nations* agreed to establish a ‘representative network of marine protected areas (MPAs)’ around the Southern Ocean. Since then, 5% of the Southern Ocean has been protected. You can find out more about Antarctic marine protected areas by visiting the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, The Pew Charitable Trusts and the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition. We are thrilled to be partnering with legendary marine biologist and oceanographer Dr Sylvia Earle in the development of our new ship. As founder of Mission Blue, Sylvia promotes exploration and protection of the ocean by advocating for a global network of marine protected areas.

How do seals adapt to Antarctica?

Seals must be some of the most versatile, adaptable animals on earth! They can survive in and out of the water, from sea level to hundreds of metres below. The deepest recorded seal dive was by an elephant seal, which went to an incredible 2,388 m (7,835 ft)! They can feed in the darkest depths, raise a pup to maturity in a very short summer and out-maneuver some of the deadliest predators alive. How do they do it?

How do seals stay warm?

Antarctic seals are great at staying warm, with thick blubber and fur keeping them cosy in the coldest temperatures.

Blubber is an amazing insulator, not only providing a warm layer of fat to ward off the cold, but also controlling the flow of blood to the skin. In cold conditions, blood vessels in the blubber become narrow, keeping the warm blood around the seal’s vital organs and away from the cold surface.

Not all fur is created equal, and Antarctic fur seals have some of the warmest fur around. Fur is made up of two parts: dense, water-resistant and insulating underfur – up to 300,000 hairs per square inch on a fur seal – and coarse guard hairs, which are longer and protect the underfur from water and abrasion.

How do seals feed in the dark?

Antarctic seals have large eyes to help them hunt under ice and in low light. Some Ross seal eyes are 7cm (2.75 in) in diameter! They also have large pupils, which dilate (get bigger) in the dark to let more light in.

Seal eye cells are also adapted for dim waters. They have lots of rod cells, which help them see well in low light, and fewer cone cells, which help with detecting different colours.

Seals also have whiskers (vibrissae), which are like little antennae that help them home in on their prey, even with their eyes and ears shut! These highly sensitive hairs can detect the movement of tiny prey in the water at a greater distance than seals can see or hear.

How do seals breed in such a short summer?

Seals have two ways of ensuring their pups survive and thrive in the relatively short polar summer.

Rich, creamy milk

Seals are mammals and, like humans, they raise their young on milk. To give their pups a strong start in life, seal milk is very high in fat. Weddell seal milk is some of the richest produced by any mammal (54-60% fat), and elephant seal milk isn’t far behind (50% fat). (Cow milk is only 4% fat!). This thick, creamy milk allows pups to grow quickly so they’re big and strong enough to face the rigours of winter.

Delayed implantation

With such a short window for growth, it’s important that seal pups are born at the beginning of summer. To ensure that seals give birth at the best time, seal breeding cycles have evolved a process of delayed implantation, which means that the embryo goes into a kind of hibernation for a few months before it starts to develop, so it will be born at the best time of year for the pup to flourish.

Do Antarctic seals migrate?

Most Antarctic seals migrate to some extent. Scientists report that elephant seals, Ross seals, some leopard seals and Antarctic fur seals regularly migrate between Antarctica and subantarctic islands. Some vagrants have even been spotted as far north as New Zealand and Australia! Crabeater seals and Weddell seals tend to stay further south, although there have been some exceptions, like this crabeater seal spotted in Anglesea, Victoria, in 2016!

How do seals protect themselves from predators?

Antarctic seals are fortunate not to have many predators. Their main predator is the killer whale.

Blubber and skin

Adult seals are protected from most attacks by their thick blubber and skin, which offers a defence against all but the largest predators, such as killer whales and large sharks.

Streamlined swimmers

Seals are beautifully streamlined to travel swiftly through the sea, using all four flippers for propulsion and steering. They can dive deep, hold their breath and often out-maneuver their predators. They can also propel themselves onto shore or icebergs, which offers some protection from water-bound predators like the killer whale – but not from leopard seals!

Perhaps the most surprising seal predator is a seal itself: the leopard seal. Leopard seals have a varied diet including krill, fish, squid – and other seals! Stealthy, skilled hunters, scientists believe they kill up to 80% of all crabeater pups, and maim 80% of those who survive! In fact, one of the identifying features of crabeater seals is the distinctive vertical scars along their flanks, which some scientists believe are the remnants of a lucky escape as a pup!**

If you’d like to learn more about Antarctic seals from the amazing naturalists in our expedition team, explore our Antarctica cruises. And if you’d like to keep reading about Antarctica, this article with 10 fun Antarctic facts is a good place to continue.

*The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) is part of the Antarctic Treaty System.

** Some scientists suggest that, as these scars are so widespread (almost ubiquitous) among the crabeater seal population, they may have a different source, for example mating or competition over mates. Little is known about crabeater mating practices.

Words by Nina Gallo, AE Expeditions’ historian and certified PTGA polar guide.

Nina has been drawn to the polar regions since her first otherworldly experience of the midnight sun in 2002. Since then she has spent time in far northern Canada, the Himalayas, the Alps and deserts in America and Australia, always seeking out quiet, wild corners to explore. She feels immensely privileged to travel to these places and shares her passions for the natural world, human stories and adventure with all the wonderful people she meets.